“Your father is radioactive,” the doctor will say after the P.E.T scan. “So don’t let him around old people or babies.” You will actually look around. All clear. No old people except your father. Very recently, he’s become old old. He’s in his sixties. He was active, even buoyant only a few months before. When this starts you are twenty-five.

There are no babies around either, but in his helplessness your father might as well be an infant.

“Okay,” you say. “Okay,” a feeble mantra, but a mantra still.

“That was not fun,” your father will say after the scan. He’ll almost smile but he’ll be too weak to laugh. And you won’t smile at all. Your father will wince and say, “Ah” several times as you help him put his clothes back on.

This is not the slow peel of age you’ve noticed in quick moments over the years: that sunny day in Flushing when he’d run into a soccer game, excited to join the fun with strangers only to come back limping a few minutes later. This is fifty-five pounds lost in two months. This is your father, a man who stood tall in his suits, perpetually ready to appear in the courtroom, suddenly laboring to move at all. His expression locked in pain and what looks like shyness but is actually just more pain, his head bowed and his eyes raising to cover the distance his neck can’t bear. This is cancer.

---

That’s what I wrote the first time I attempted to make sense of the experience of supporting someone living with cancer. I put it in the second person because the first person was too close.

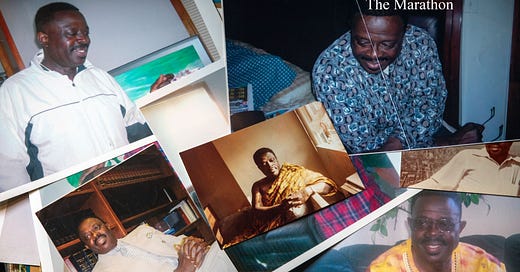

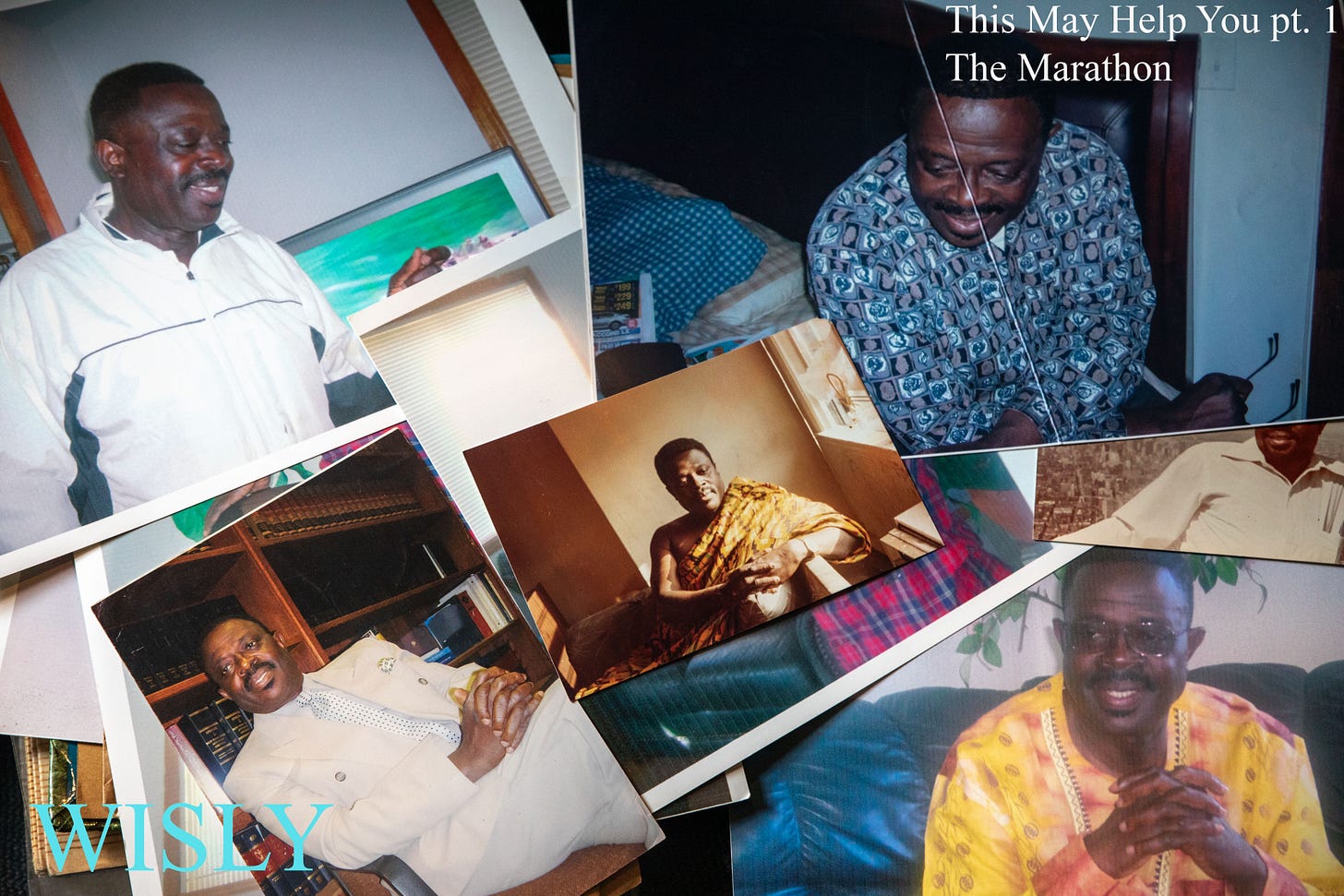

I later spent several months writing in a bakery in Syracuse, revising what I thought would be my definitive reflection on a challenging period that I’d eventually emerge from triumphantly. Things changed. In the interim, about two years, I’ve felt peace at times, but mostly it’s been struggle. In the time between my first series of attempts to write this essay and my second round of more earnest attempts, I’ve become an author in a different sense. My first published book now exists, in multiple languages. I’ve gone from existential dread at the thought of flights to complaining casually about jet lag. Lately, and for the better part of the last two years, the word “Congratulations” fills the space that used to be occupied by “Hello.”

And now it’s been about many more years. This is me, Present Nana. I never put the essay out those years ago because I just didn’t have it in me, I think. I didn’t want to deal with an external editorial process maybe, although I did get feedback from Naomi Gibbs, me editor and Meredith Kaffel Simonoff, my agent.

What I’m saying is this is the third and final phase of trying to work through this essay. I tried once while it was still happening, it being my father’s cancer, then I tried again two years into being his proxy through the process and now I’m putting out what I wrote about nine years after he started getting treatment. I was 25 when it started, as you’ve read, I’m 34 now.

I think I’ll create a system where regular WHITE is the original timeline.

Italics are the SECOND PASS 29 year old Nana

And Big bold is PRESENT. On Audio I said colors but Substack isn’t letting me choose colors smh.

Many things have changed. When I first put these thoughts to paper, my father was still alive. It’s also worth inserting, I wrote the all but a few sentences (like this one) of this essay before the world was thrust into pandemic. There is a new context to the loss. An more precise understanding that grief can be communal, that flavors of the same dread can move through us all at once.

But my father has been gone now for more than a year now. I’ve felt so much in that time, as we all have. And I have come to know this, which may help you: Grief is slippery. Grief is a shadow, a shapeshifter.

Incidentally, the bakery I wrote in has since closed.

---

The P.E.T scan was not the first time I’d accompanied my father to the hospital. Some years before, he’d complained of a pain in his arm. “It may be linked to heart problems,” he’d said. I drove and he’d hardly complained. His silence was stressful. I throttled ten and two, slowed to the speed limit. A sixty-year-old Ghanaian man silent for an entire ride as his son drives his car: a sure sign of real trouble. I was an undergrad. I remember doctors calling him, him disappearing somewhere for what couldn’t have been long but felt like hours. I remember them pulling the curtain back, I remember him there in a dotted sheet dress, his ankles and shins poking from the bottom of the gown. A nervous smile on his face. They’d run tests. His blood pressure was a little high, he was diabetic, but hardly so. “Keep doing what you’re doing,” a doctor had said. He was as “healthy as an ox.” The doctor’s voice suggested compliment, surprise even. I was surprised too. My father was a mountain. A constant. A thing to triumph in the face of. Now, suddenly, he was healthy, but still part of the herd called human.

(Looking back over a decade later at this instance I wonder if that doctor was bullshit. I wonder if the seeds of what would kill my Dad was there and he just didn’t see it. Like maybe we’d been given a warning, a chance.)

Years later, he called, and afterward so much was different.

(So that first instance I was in Undergrad. When I got this call I had finished Grad School)

“So, they’ve run the tests, and it is lymphoma. They say it’s what they call diffuse cell lymphoma.”

Now, more than two years after that call and a year after my first attempt at this piece, what hurts me most was how even his voice was. How strong. I wish very badly that I could have told him then that it was okay to be scared, and that I was scared too.

In the moment, I made certain not to say, “What?” or “Huh” which, in the way children learn their parents, I’d learned is the kind of small thing that could upset my father.

“What is huh?” he’d yelled at me often as a child… and as an adult.

“Okay,” is what I said instead. Feeble, trusty mantra. “Okay,” and with a flatness that in the moment made me a little proud. A flatness I now regret because it confirmed that yes, we would handle this the way we handled everything. Stoically. Logically. Systematically.

I stood up from where I was sitting because it felt like I should be standing for something like this.

Confident and direct, I asked, “Is there a plan?”

---

And in that moment, you look up and discover the huge blade of an axe on a pendulum. Its head ornately decorated with jewels red and gold, its steel gleaming and bright, hovering in the sky above you at about one o’clock if where you are trying to stand is six. It is far off but you can see it so clearly. Has it always been there? Yes, it seems it has always been there, but now you can see it perfectly. And as you stare taking in its perfect power, you know intimately it is coming for your skull. You notice it inch forward, down. It creeps slowly then stops. Still far off, but no longer hiding, no longer dormant. It follows you everywhere you go.

The axe thing was a part of my first swing at a draft. Now it strikes me as “writerly,” but in a way that really means “false.” Like I’m trying to prove I can describe things. I didn’t feel like there was some magic axe trained on my skull. Or maybe I did a little, but now the noting of it feels unnecessary. In trying to assign proper power and reverence to what is difficult, I went, first, for something grand. Something ornate, beautiful even. But now, in these moments after, I know now that the truth doesn’t lie in jeweled axes, but in saying things plainly. It hurts more.

I second this note from my past self.

---

Whatever the doctor’s plan was, I decided that I had to finally become a real author in response to the diagnosis. That was my plan: success away the cancer. I had just recently graduated from an MFA program. If I worked hard it would be okay. This was the crisis I’d trained myself to always expect. This was another form of not having enough money. An eviction of the body from itself, rather than from a home.

This was the situation I set up because this is what I knew.

This is how my mind sculpted the problem because this was what I understood.

I promised myself I could fix it. I would fix it. Within a month I had found the woman who would become my agent and in another three months we had sold the manuscript that would become Friday Black, my first book.

---

In the beginning, I used the word “lymphoma” almost exclusively. It had a more clinical sound, and by my pathetic logic, was therefore more likely to pass. Cancer killed. Lymphoma, I hoped, came and went. A storm, a bad one, but one that never threatened the blue sky it blanketed. And so we went into the storm named Lymphoma.

What I didn’t expect is how boring much of it would be. And how strange it is to be both mortified and bored in the same moment. Lymphoma was a waiting. It was document producing: Naturalization papers, Social Security Card, Tax information. It was a gathering. Every piece of paper ever, it seemed, to prove my father was eligible to pay for his life. Lymphoma was a slow, expensive dying.

---

A man called Doctor K explained on the phone that he would be the quarterback in this campaign for my father’s life. He’d learned from my father I would be his go-to for most things. The General Manager.

“Diffuse cell? Is that right,” I asked, scribbling frantically into the notebook I’d designated for my father’s medical stuff. In it, I stored all knowledge and tips I received regarding the disease. On one page in that same notebook, the words “Long game” and “Marathon” were written over and over. Another stronger pair of mantras, given to me by a friend who also knew what it was to shepherd a father in sickness.

“You have to pace yourself,” she’d said, “this is a marathon. Play for the long game.” I didn’t listen at first and I paid for it.

So, this may help you: It’s a marathon. Pace yourself.

“Diffuse large cell lymphoma,” Doctor K had said. “There are treatment options. It has about a fifty percent survival rate.” As he spoke, I felt the skin of my neck and chest tighten, as if to choke me.

“Okay,” I said. A fifty-percent chance. A coin toss. Live Dad. Dead Dad. Call it in the air.

For various reasons, I was given legal power. I am a middle child.

---

In the early drafting phase of this piece, I’d included a pretty angry retelling of how it came to be that I was the person who did most of the work regarding my father’s health. Looking back, I know this: The one who does the work is the one who can. And if you are that child, that friend, that person, I believe you should ask for help in all the places you need. It may not come from the obvious places. This fact, that everyone won’t be able to help in the same ways, is a truth I still struggle with. I remember asking for help. When it didn’t come as I hoped, I thought to explain that the help would be for me, not for him. But I didn’t. Instead, I accepted the choices of the people closest to me. Not because I’d achieved some enlightened state through exposure to suffering. This is important to remember: Cancer will not make you or your loved one better people. Not in and of itself. I didn’t fight. Not because I wasn’t angry. I was angry, but more than that I was tired.

I have more thoughts on this but I don’t even know where to start.

And yet I discovered I had so much family. I knew this, but I discovered it anew. The ones abroad and out of state emerged in service. For them I am truly grateful. They had words of divine encouragement, “God will see us through. God is faithful.”

“Thank you, Aunti,” I said.

“Thank you for helping your father. God will Bless you.”

“Thank you, Aunti.”

Marathon.

Early on, we got a walker for free from the Ghanaian physical therapist in the hospital. “Don’t tell anyone,” he said in English. Then, he continued joking with my father in Twi about how limited I was, how much I was missing, living exclusively in the language of an oppressor.

“Thank you,” I said, as my father, laughing with the physical therapist, struggled to raise his arms and slowly turn his palms up to the sky in jest as if to say, “I tried my best.”

I’m putting out part 2 of this essay because it’s a long one. But thanks for finally giving this piece a home you, whoever is reading. I hope you don’t need it, but if you do, my heart is with you.

The one who does the work is the one who can.

I find a first draft in second person POV feels the most natural and “safe” when writing about hard things. Especially family related. Maybe it’s like stepping outside of yourself as a participant?

I appreciate the layering here of different perspectives. Thank you for sharing the vulnerable parts here.